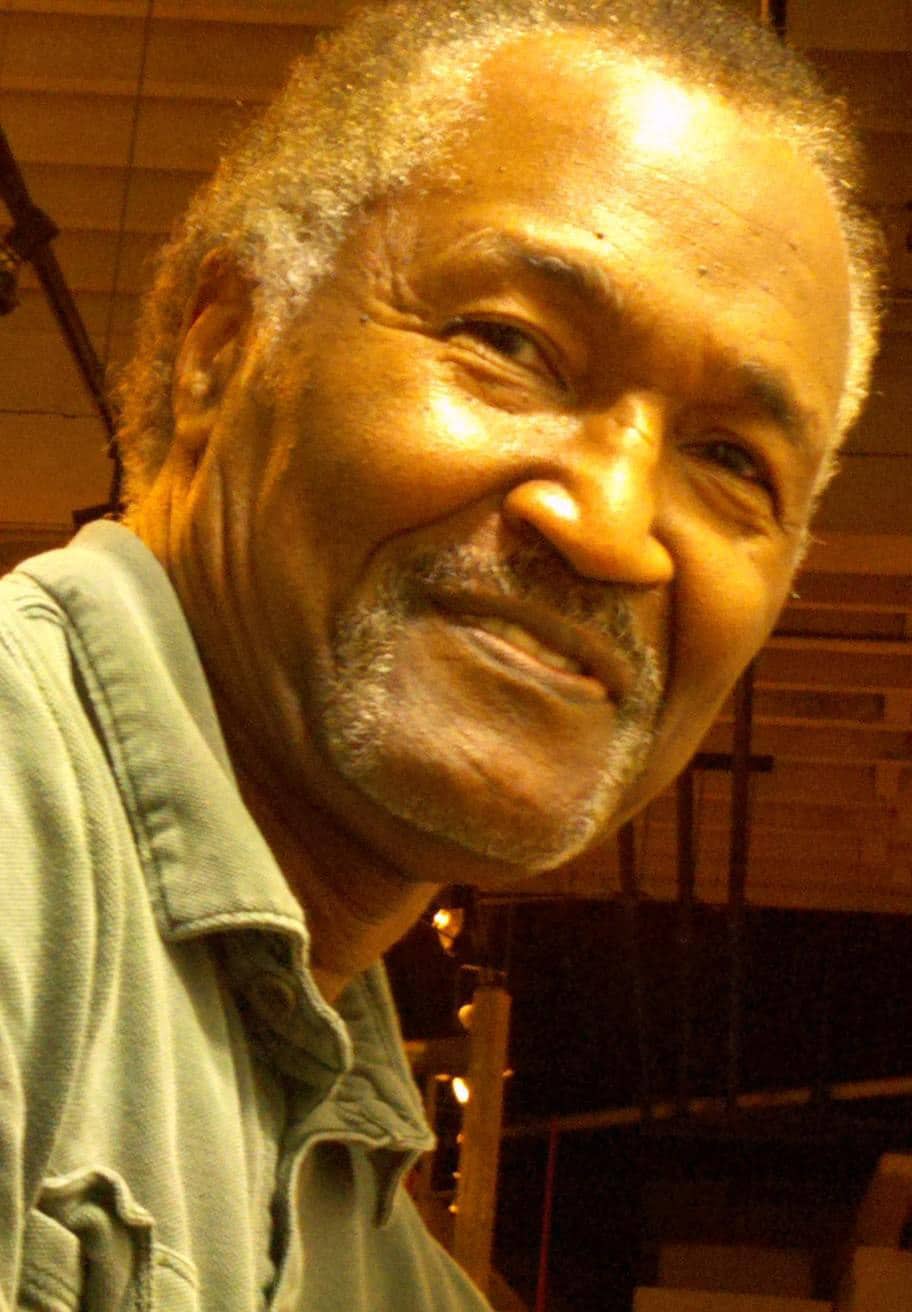

For our first edition of 20 Minutes With, it seemed inevitable that we begin with our foremost resident artist and local Renaissance Man Preston Jackson. In addition to founding the Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, Preston has been playing guitar, sculpting, and painting in the Midwest for decades. He won a Regional Emmy for hosting Legacy in Bronze, which featured sculptures from his show Julieanne’s Garden, and received the state’s highest honor by being named the 1998 Laureate of the Lincoln Academy of Illinois. Preston sat down with Parker Biederbeck for 20 Minutes to talk about his new show, Beyond the Garden, and some of the insights he has accumulated over an enduring and versatile career.

NOW: Thanks for taking the time to speak with me. What have you been exploring with your recent work?

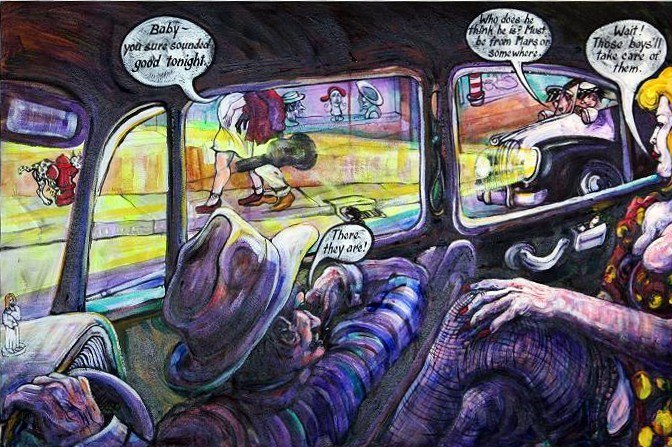

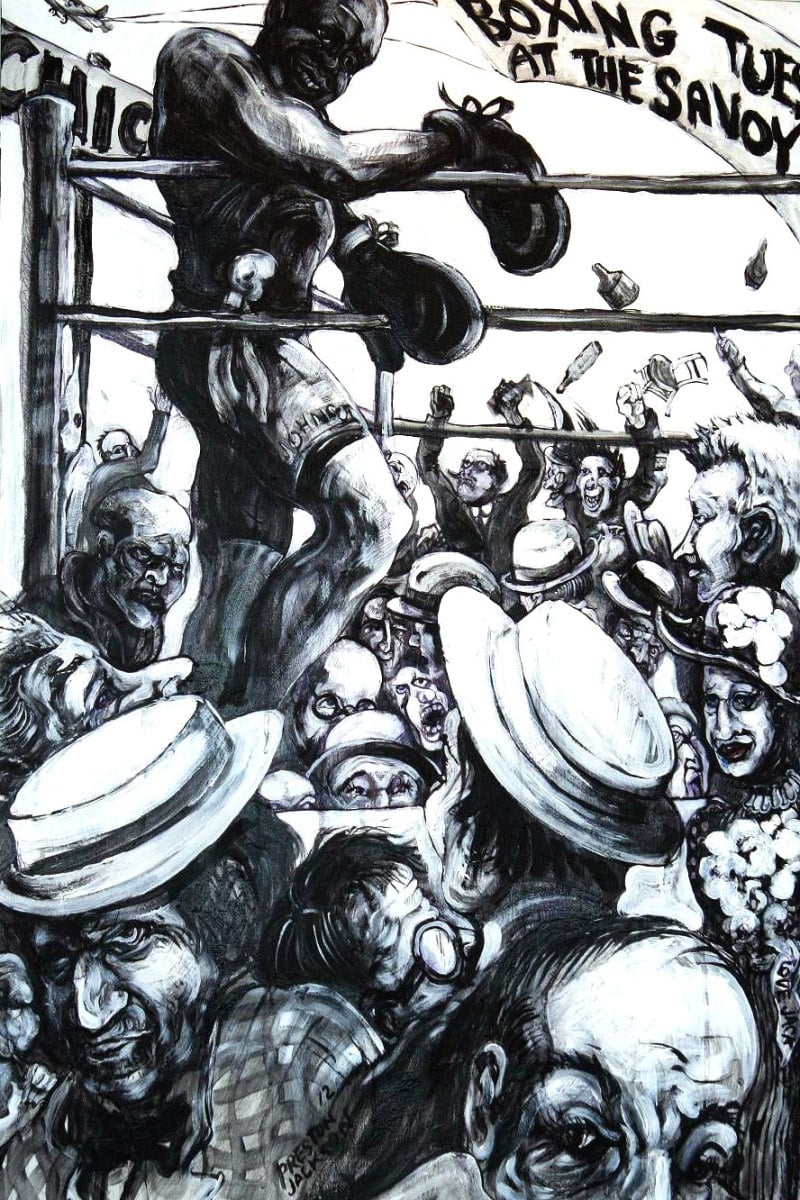

Preston Jackson: It’s about the concept of racism. Not my own experiences specifically–it’s about that whole idea of differences. Some people call it racism, some people call it bigotry. The height of problems between us, socially, revolves around our disimilarities. In many places–Israel and Palestine for example–the people look the same but have “religious differences.” They look exactly the same. It’s so absurd. It can be as minute or undefinable, unrecognizable as that. Or it can be very tall people versus the very small, like the Tutsis against the Twa people. It could be a big contrast between physical differences.

NOW: Or it could even be just a smell.

PJ: Just a smell! We’re all the same. We’re human beings. We’re all capable of thinking and doing and living and being the same way.

NOW: In the paintings from Out of the Garden, I might have noticed the spectre of Edgar Degas or Toulouse Lautrec—what looks to be the expressive recording of a wild, decadent nightlife. Are you exploring a particular moment in black history?

NOW: In the paintings from Out of the Garden, I might have noticed the spectre of Edgar Degas or Toulouse Lautrec—what looks to be the expressive recording of a wild, decadent nightlife. Are you exploring a particular moment in black history?

PJ: That’s when it becomes very, very personal. Meaning that I paint who I am. That sums it up. I think all artists who choose to be creative should be true to what creativity means. It means communicating. Communicating certain internal things, you know? It might be that you’re highly attracted to history, like the Industrial Age or the Civil War, but you must look deeper and see what connections you personally have with this and what inspires you to be passionate about it. My work, although most of it is centered in times way before my own, still connects to the present. So I record my reaction to those things in who I am. That’s why you see a lot of African-American faces and physicality in my work.

NOW: So you would say they are all facets or aspects of yourself?

PJ: Yes. Even though I was brought up in an area that was somewhat integrated in Decatur, Illinois, it still reflects the people I’ve been around. There were Germans in our neighborhood, there were Japanese, but most of my childhood was African-American. So I go back deeper into the stories that were told to me. About slavery, about my parents and grandparents, and about hard times—Reconstruction, the Talented Tenth. The whole idea of social systems being divided within themselves.

NOW: So there is a whole mythological landscape you’re working with that came from your family and from your own oral history?

PJ: Right. A historical and personal map of references. As true as I know them to be. Obviously, we are all equipped with our own opinions on how we feel about things, so of course I’m going to inject that into my work.

NOW: Hasn’t history always been a subjective experience?

PJ: Yes it has. There’s a lot of good to learn from our history. I think it’s the charge, or task of the artist to challenge, to be vigilant, to teach.

NOW: I notice in your work there is a certain grotesqueness to the figures, in the sense of their proportioning or body language. From where did this emerge? Are you perhaps experiencing yourself through another’s gaze?

PJ: You did mention Degas, and other artists of the period, like Toulouse-Lautrec, or Gaugain. All artists of various eras, individually, see the human form in certain ways. Just like we do landscapes. We interpret and process things through our own mind’s eye–what things feel like more than how they are visually represented. The things that seem distorted proportionally, I think of them as beautifully suggested in bringing out the stronger qualities of that particular body. Emphasizing.

PJ: You did mention Degas, and other artists of the period, like Toulouse-Lautrec, or Gaugain. All artists of various eras, individually, see the human form in certain ways. Just like we do landscapes. We interpret and process things through our own mind’s eye–what things feel like more than how they are visually represented. The things that seem distorted proportionally, I think of them as beautifully suggested in bringing out the stronger qualities of that particular body. Emphasizing.

NOW: What is your own creative process like? Do you write?

PJ: The process begins with a mark on a white sheet of paper, a brushstroke on a canvas. You analyze or feel the power of that particular mark, depending on how it was put down. How much force it took to get that ink transferred, or some other quality. The most important thing, because that’s the mechanical part, is to connect the mental with the physical and understand the reaction of not only yourself, but your audience. It’s a little Zen-ish. That’s where it begins. From there you become either emotionally connected in some way, or infatuated, or it’s a repellent kind of feeling. But all of those things are part of life and you need to be the one who “wields the sword.”

NOW: How do you approach sculpting? Do you begin working out a form from the clay?

PJ: It begins in the mind. It could be the first inklings of light coming through a window as you’re waking up. It could be the first sounds you hear after your consciousness returns after resting, which sleep gives us. Or it could be a notion that can be captured quickly while it’s fresh, and spat out. Or materialized very quickly. The art begins not necessarily with materials, like clay, or drawing or that stuff. It begins in the mind. You think first and then you act. But you are responsible, at some point, for the results of those actions. Whether it’s too forceful, or too much this-or-that. You have to think about your audience’s reaction to your work. Therefore, you are manipulating, planning, and designing, not just with your tools for making things, but with the response of your audience. Put these people here, put these people over here. Gently whisper to these people, and shout to these.

NOW: You’re like a shaman almost, in how you work. It seems like you have a lot of trust in your subconscious. You allow the world to filter through and flow out of you very freely.

PJ: I guess whether or not they want it to seem that way, an artist-shaman is a teacher.

NOW: They’re the brave ones who take that first step to show the way.

PJ: Right. That’s why they float to the top. We put them on pedestals. Sometimes we put the wrong ones up there.

NOW: I have a hard time imagining where the art world is headed. It’s so commoditized now.

PJ: It’s so political. This is what I liked about the Riverfront Museum downtown. The very first show was a showing by all artists involved. There is a new group in Peoria that is taking on this concept that everyone’s work is important. So they bring as many different backgrounds and artists and media as they can into the forefront. That’s their goal. I think it was a very wise move.

NOW: Do you have any work in the museum?

PJ: I have a couple of pieces there. There is a large piece we’re auctioning off to raise money for the museum. But I enjoy seeing pieces by artists who don’t really get the exposure they deserve. They are doing wonderful work. It’s a learning thing for me—get out there and look at their work.

NOW: That brings me to my next question. I know you teach at the Art Institute of Chicago. How does that experience inform your work?

PJ: I’ve taught there for about 25 years. I’m actually Professor Emeritus. So I’m a little more in control my schedule, but at the same time I reap the benefits of student teaching–meaning that students are teaching me as well. I’m able to give them stored-up information and experience from many years, and it just pops out of me. I have nothing else to do with it, you know, so I share it with them.

NOW: And they can give you something that is untainted too.

PJ: Their reactions, their responses to what is coming from me to them. Their reinterpretations. Their new perspectives and freshness. Nothing can be contained, things splash around. When it does I grab a little piece of it and rub it on my face.

NOW: Haha. We all know you are a talented jazz guitarist and you’ve played around Peoria for decades now. How does that influence your work? The rhythmic qualities of music have been very important to painters and sculptors. Do you have any personal experiences about how those disciplines complement each other?

PJ: I don’t make a strong division between the arts. If you’re a painter, you should sculpt. If you sculpt, you should draw. If you draw, then you should make videos. All of those things contain the same elements. I’d go a step further and say it’s the same with audio arts and the visual arts. There are elements they share. It’s just a matter of knowing how to work these formulas to get an effect. Not as a strict mathematical formula that always has to come out “even” or “right”–no such thing as right or wrong. Free, open-form music is to me, like a Jackson Pollock painting.

NOW: Pure expression.

PJ: Nothing is wasted. The creator of the universe within the universe within the universe… She or it had a plan, a real nice plan. So many things are much larger than human beings. They had a wonderful plan and it’s left to us to figure it out and use it.

NOW: The universe is playing through you.

PJ: All the time.

NOW: Do you have anything about your upcoming show that you would like to add?

PJ: Just come see it. Come with an open mind and see the work. It’s not about me. It’s about people. It’s about human beings. It’s about what I want them to see–treating each other with kindness and respect. I try keep who I am, all of this stuff, in perspective. I am no different from some guy in the Philippines. We’re no different. I have a family, he has a family.

The public is invited to a free Gallery Talk with Preston Jackson on Sunday, December 9 at 2:00pm.

The public is invited to a free Gallery Talk with Preston Jackson on Sunday, December 9 at 2:00pm.

Visit Preston’s official site to see more of his work.

“Beyond the Garden” was exhibited at the Contemporary Art Center of Peoria, where Preston maintains a studio and exhibition space.

Top photo by Bethany Mitchell