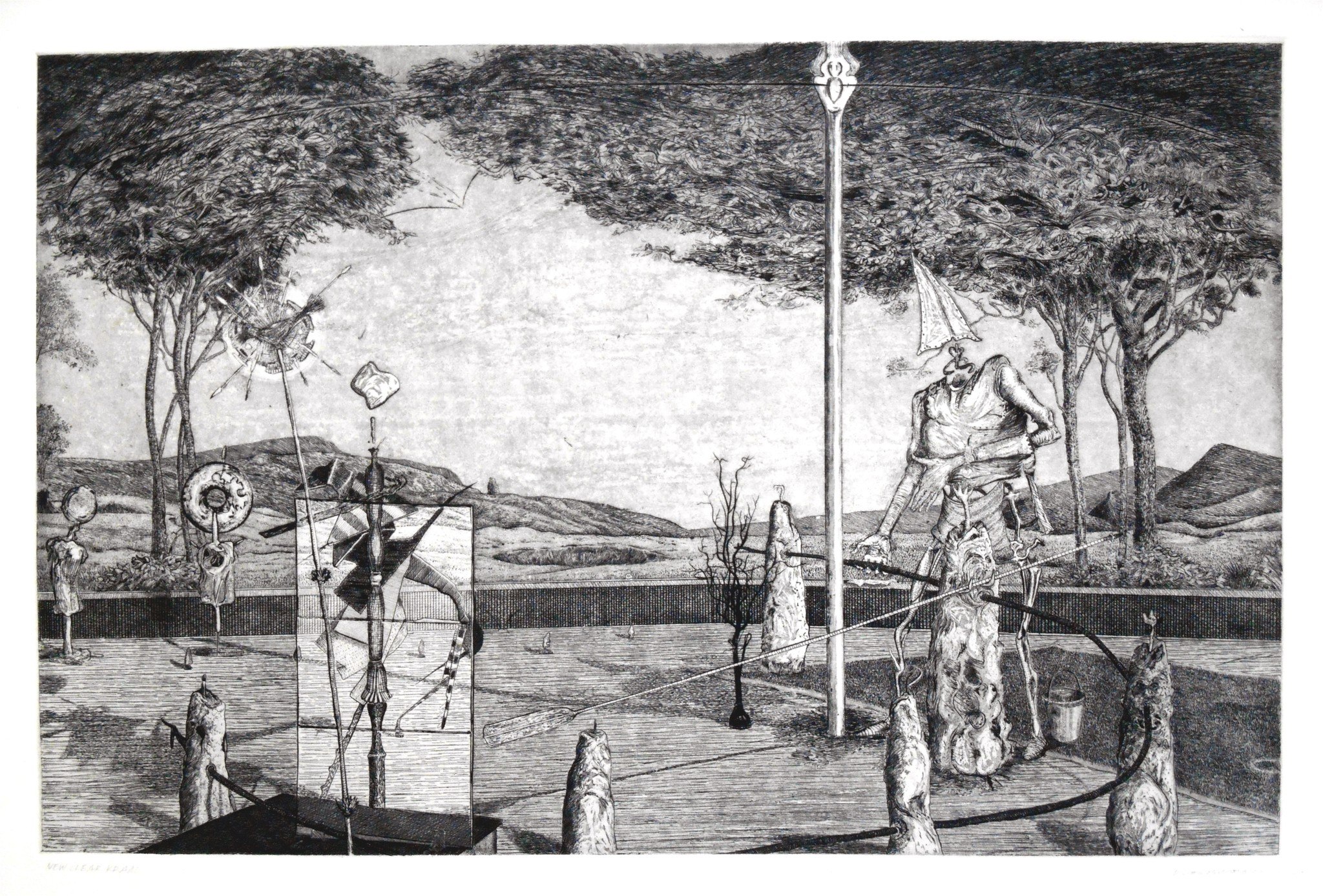

If you have ever strolled in through the rear entrance of the Contemporary Art Center, chances are you’ve met eyes with an aproned, serious-looking man quietly gouging away at metal plates. Perhaps he was lugging tubs of cloudy acid, or arrays of gleaming picks. These seemingly harsh tools fill the laboratory of etcher Chris Holbrook as he creates images intaglio, to be later printed onto paper. Chris best personifies the artist as mad scientist, as ceaseless searcher of experience, as alchemist. Fiercely independent by nature, he does things his own way. We’re lucky to have him passing along his insights as a lifelong artist to students at the CAC and delighted to sit down and chat with him for an enlightening 20 Minutes.

Parker: How did you get involved with the Contemporary Art Center of Peoria?

Chris: Well, I heard they had a press. It was under a tarp without a dedicated space, so I asked Patricia Keck if I could come down and use it without having to rearrange things just to get access. She worked with the board to open up some space for it and before long (Executive Director) William Butler approached me to consider teaching a class. I love it. There are some people who get really dedicated to it.

P: When you started teaching, did that change your own work?

C: I think that the influence of teaching can take a long time to affect a young teacher as to how they do their work. But I think it does, eventually. You have to force yourself to teach the fundamentals over and over again. Teaching is sort of a reciprocal engine: the more you teach, the more things you pick up from your students. When you really hammer them sometimes on particular aspects they sometimes come up with solutions that you wouldn’t have. I think those experiences oftentimes take a number of years to emerge for young teachers.

P: Are instructors somewhat resistant to that side of it?

C: It’s something that becomes more visible as you evolve as an artist. Sometimes the influences you pick up can be lots of small, little things. Subconscious stuff creeps in. We learn all kinds of things, not necessarily what you think you’re learning. Kids learn behavior from their parents that they didn’t intend to teach, but are passing along anyhow.

P: What do you teach at Bradley right now?

C: I’ve been teaching beginning drawing courses for a while, but I have taught a lot of figure drawing, a lot of advanced drawing, intermediate drawing.

P: How about the classes you teach at the Contemporary Art Center?

C: Monotype, etching, drawing fundamentals for children. The last is sort of a drawing/design class. They need to be praised and not pushed too hard. It’s important that kids make art in a way they enjoy. Picasso said that when he was twelve years old he could draw like Raphael, but he spent the rest of his life trying to learn how to draw like a kid again. His father was an artist and he really learned to do academic work that got him into school.

P: But you can get kind of trapped in that, no?

C: You do. You do. A lot of artists have told young students, “Don’t go to school. It’ll homogenize you. It’ll academicize you and you’ll be making academic work.” That is, as opposed to following your own direction and picking up things by looking at other artists. Trial and error.

P: Do you think an artist needs to go to school?

C: Yes and no. It’s hard to say. You live in a community, and in that community you are influenced by some of your fellow students, some of your fellow professors. You learn to watch what other people are doing too. There are good aspects in going to art school, as long as you have the drive to do it and are open to change. Some people enjoy doing the academic approach and then bring a personal or contemporary vantage point into their work.

P: Who are some masters or galleries that you recommend to those interested in learning etching?

C: Rembrandt is always one of them. The big three are Rembrandt, Goya, and Picasso. The Davidson Gallery in Seattle is a very printmaking-heavy gallery. There are a lot of contemporary printmakers from Europe, America and Asia that show their pieces there. The big collaborative workshops have great work. There’s a place called Crownpoint Press in San Francisco. There’s a place called Universal Limited Arts Editions in New York City. The Tamarind Institute in Albaquerque, NM. There’s a place in Chicago started by Jack Lemon, Landfall Press.

P: Where did you go to school?

C: I went to Western Illinois University. I got a degree in Commercial Art Illustration and I fell in love with printmaking, specifically etching. I moved to Florida shortly after I graduated and worked as a graphic designer doing airbrush photo retouching, product photography, layout and illustration. So I had a job that was very diverse and I enjoyed it for that reason. I got experience doing technical illustration, situational illustration and a lot of catalogue/brochure design.

P: What company did you work for?

C: I worked at one place in particular in Florida called Audio Intelligence Devices. It was a manufacturing facility, the world’s largest manufacturer of intelligence-gathering devices. I worked there for almost seven years. I wanted to come back to the Midwest. My dad got sick and didn’t make it for very long, so it was good timing to come back. I met Oscar Gillespie at Bradley University and decided to return to grad school and attempt to get a teaching position.

P: Was Oscar your inspiration to teach?

C: Yeah, at first. I had just been accepted into the program at Bradley and it was a good segue getting out of Florida, trying to develop myself as a teacher. I found I wanted to go further. I’ve taught over fifteen years now.

P: Were you still making art for yourself while you were working as a designer?

C: I was. I was. I started doing some acrylic paintings. I took a couple printmaking classes at Florida Atlantic University and Broward Community College. So I kept my hand in it a little bit. I was really excited to come back to Bradley and throw myself into etching again. That’s what I did.

P: How did you pick etching to focus on? What about it drew you?

C: The fine line quality of it, being super detailed. The fact that you can etch a line for just a minute and it’s barely, barely there. I loved all those technical things that you can do with a piece of metal.

P: How would you break down some of the advantages and disadvantages of etching versus lithography?

C: I had an affinity for working with really fine detail. Not so much crosshatching and shading. Lithography has more of a “drawing-with-a-pencil” kind of look to it. It was interesting but it’s very complex to print, whereas etching is more complex to get the image onto the plate and produce the effects you want, but printing is relatively simple. Oscar at Bradley also did etchings and engravings on the same kind of plates, so I was influenced in that respect.

P: Are drawing skills important to learning etching? If somebody wanted to get into etching, might they be better off taking drawing courses first?

C: Yes. If you don’t draw at all, you should learn to draw before you take etching.

P: Have you done pottery or ceramics?

C: Yes I have done a lot of ceramic sculpture. I don’t really throw on the wheel, though, ever.

P: What excited you about ceramics?

C: Three dimensions. You don’t have to draw shading. Light hits an object and casts a real shadow. You don’t have to work at creating an illusion. I love manipulating clay. I started throwing down clay on my woodcuts. I would put it in my car and drive around looking for textures. I’d throw big slabs against surfaces and then take them back and cut them up, stretch them out, add other textures. It’s funny because the ceramics affected my printmaking, and the printmaking affected my ceramics. I could do a drawing in wood and then gouge the drawing out with some pretty deep cuts. Then I could throw the clay down on there and have a pretty sophisticated drawing instantly on the material.

P: How is Peoria as a city for artists? Are there things about it that make artists want to stay here and be part of the community?

C: Studios can be very inexpensive here. Sales can be tough, but it’s close to St. Louis. It’s close to Chicago. It’s close to a lot of other big cities that have clients who buy art.

P: What type of work have you produced for shows? Mostly etching?

C: A lot of drawings. And prints, but not necessarily etchings. I’ve been doing one-of-a-kind collagraph mono prints. The difference between a monotype and a mono print is that a monotype has nothing fixed. Nothing is scratched or cut into the matrix from which you make the print. The matrix can be a piece of zinc, cardboard, plexiglass. You can do a painting on a piece of plexiglass then print it. There’s nothing that’s fixed into it. So I make mono prints. I use two or three different matrices sometimes, then I print on top of this quilt-like design of different papers and fabrics that I glue together.

P: So you are going beyond etching?

C: I’ve really kind of worked on developing this technique. I came into an enormous amount of matteboard scraps, started experimenting, and have just continued to work with it for over ten years.

Chris Holbrook has taught art for over fifteen years and practices independently as an artist in Peoria, IL. Contact Chris and see more of his fantastic work at the CIAO (Central Illinois Artists Organization) site.